The Medium is the Metaphor

Neil Postman's tech and media criticism and its relevance for the 21st century

If you’ve been within a 20-foot radius of me lately, you’ve probably heard me rave about the late, great Neil Postman. A social critic and communications professor at NYU, Postman wrote voluminously on many topics, including propaganda, language, and the purpose or “end” of education (to produce competent “crap detectors”, that is, to instill in the youth a strong capacity for critique; while at the same time nurturing a healthy democratic citizenry by uniting them around a positive common narrative). But his magnum opuses “Technopoly” (1992) and “Amusing Ourselves to Death” (1985) critique reflexive techno-optimism and the corrupting influence of electronic media on public discourse. And in 2025, they feel more urgent than ever.

It’s no small tragedy that Postman died in 2003, just before the rise of smartphones, social media, and, a bit later, consumer-grade generative AI — though I suspect if he witnessed our current technological landscape, he’d promptly request a return to the grave. Short-form videos with flashing graphics and quick, frenzied cuts have become our primary way of consuming content. Hyper-personalized algorithms decide for us what we should see and what we shouldn’t. Billionaire tech executives have unprecedented power over the minds of billions, and they’re duking it out for control over the future, smashing through ethical and environmental protections for the sake of technological progress — which, now even more than in Postman’s time, is viewed as an end in itself, rather than a mere means.

But let’s take a step back here. What exactly did Postman have to say about technology and media? Why did he seem like such a doomsayer? Why should we take seriously his seemingly pessimistic outlook, given that technological progress and new forms of media have made life so much easier, better, more efficient, and more entertaining for just about everyone?

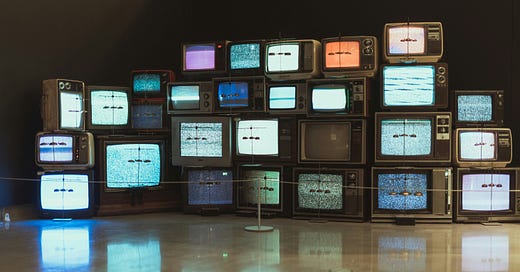

Let’s start with “Amusing Ourselves to Death”. Written in the mid-1980s at the height of television’s popularity in America, in it Postman laments the way the medium of television encourages people to engage with serious topics as if they were merely a form of entertainment. He thought television trivialized information, turning politics, religion, and education into a kind of vaudeville act.

Postman took great inspiration from the philosopher Marshall McLuhan, who coined the phrase “the medium is the message” in the 1960s. Critics of new media tend to focus on the content we see on these platforms. We hear things like, Twitter is toxic because it platforms bigots or Instagram is hurting kids because they’re seeing their friends out having fun and it’s giving them FOMO. These critiques are often true and important and valuable. But they also tend to overlook the possibility that the medium itself might have something to do with how we experience its content, and in turn with how we experience the world more broadly. By focusing only on the people who say harmful or misleading things, or on the tech companies who allow such things to be said, content-focused critiques forgo examining how the way we consume information might affect us just as much as the information itself.

McLuhan thought that the form of the media we consume, whether it’s a book, a radio broadcast, or a television program, actively shapes our experience, over and above the specific content we’re reading, listening to, or watching. It’s not that the content doesn’t matter. It’s that what people say on television or post on social media shouldn’t distract us from considering the way the medium itself demands certain kinds of engagement, promotes certain habits of thought, and, depending on its level of integration into the culture, creates an environment or “ecology” that directs the way we understand the world. And it does so without our being fully aware of it.

Of course, content matters hugely. We want people to be creating and spreading content that is generally true and helpful and beneficial for society. At the same time, we need to be aware that no medium is truly neutral, and that certain kinds of content thrive more than others on certain kinds of media. So, yes, Twitter is full of misinformation and hate speech, but that’s not just because people are dumb and mean or because its designers are deliberately censoring or promoting certain kinds of content (though this may be the case, too). We might say that, as a medium, Twitter itself — with its character limits and algorithms optimizing for virality over integrity — promotes, demands, encourages, incentivizes creators to present information in a very specific way and users to behave and see the world in a very specific light. The medium plays an important role in how its content is perceived and interpreted, implicitly embedding its own message about what the world is like and how we ought to interact with it. The medium is the message.

Postman modified McLuhan’s original claim slightly, advancing the subtler claim that “the medium is the metaphor.” In Postman’s view, media aren’t “messages” in a strict sense because they themselves don’t make concrete statements about the world. Rather, media work more like metaphors, using “unobtrusive but powerful implication to enforce their special definitions of reality.” He wrote that “our media-metaphors classify the world for us, sequence it, frame it, enlarge it, reduce it, color it, argue a case for what the world is like” (AOTD, p.10). We might say that different media have different epistemologies — different ideas about what counts as knowledge and how it is to be obtained.

"The medium is the metaphor."

- Neil Postman

Let’s get concrete. In an oral culture, that is, a culture which communicates primarily through the spoken word, concepts like truth, wisdom, and intelligence are wrapped up in the ability to recall aphorisms and proverbs. To forget, in such a culture, is not only considered stupid but is also often dangerous. There are relatively few oral cultures today, but they were the default before the advent of print.

Meanwhile, in a print culture, where long-form books, letters, newspapers, and other forms of the printed word dominate, high value is placed upon argumentation and the “coherent, orderly arrangement of facts and ideas” (AOTD, p.50). This is not to say that all or even most writing in print cultures is logically sound or analytically rigorous, but rather that what rises to the top in print culture, what is encouraged and rewarded in print culture, is the rational, detached, objective ordering of information. Print places demands on readers, too, who “must come armed, in a serious state of intellectual readiness”. Postman notes that “To be confronted by the cold abstractions of printed sentences is to look upon language bare”, and therefore that “reading is by its nature a serious business” (AOTD, p.50). The dominance of print creates a certain kind of media environment, one that values the kinds of serious discourse afforded by the printed word.

Print culture reigned supreme in large-scale societies until around the 20th century, when the prior century’s inventions like the telegraph and the photograph created the perfect conditions for a revolutionized media landscape. The telegraph allowed information to be transmitted virtually instantaneously for the first time in history, unbound by geographical distance and entirely devoid of context. Meanwhile, the photograph allowed for visual scenes to be captured and disseminated en masse, and importantly, without the use of abstractions or arguable propositions. Photographs cannot generalize or make claims: a picture “does not speak of ‘man,’ only of a man; not of ‘tree’ but only of a tree” (AOTD, p.72).

The rapid spread of decontextualized and often irrelevant information, combined with the rise of imagistic representation through photographs, found its perfect expression in television. If each new medium “changes the structure of discourse… by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain kinds of content” (AOTD, p.27), then the structure of discourse promoted by television revolves around immediacy, visual stimulation, and emotional engagement.

Crucially, television, for Postman, is a perfectly acceptable medium on which to broadcast and consume explicitly entertainment-focused content. Shows like Cheers and the Diff’rent Strokes (two popular sitcoms in Postman’s time) were not the problem. In our times, he’d probably think that trashy reality shows and binge-able Netflix dramas are totally fine. Because that’s what TV is best at: pure entertainment. That’s what it should be for.

The real danger, Postman insists, is when TV is used to conduct serious business. When preachers adapt their sermons for national networks, when political debates take place on 25-inch displays in people’s living rooms, when book-reading is replaced by entertaining videos in classrooms, something subtle but troubling happens to the topics at hand.

Recall the idea that different media have different biases. Whereas the printed word biases “logic, sequence, history, exposition, objectivity, detachment, and discipline”, television biases “imagery, narrative, presentness, simultaneity, intimacy, immediate gratification and quick emotional response” (AOTD, p.16). Because of the way television works, because of the kinds of content it affords and the way people tend to engage with it, producers must adapt their messages to meet the demands of show business, which rarely line up with, and indeed are often in conflict with, the demands of serious discourse. The real danger is not Cheers but NBC Nightly News; not Diff’rent Strokes but Sesame Street (Yeah. Dude was not a fan of Sesame Street).

Since no medium is neutral, it’s not as if taking a speech that would have occurred on the radio and instead broadcasting it on TV keeps the original message wholly intact. A shift in medium changes how the message is presented and received. Consider, for example, how the nature of the political debate has changed over the centuries. In Lincoln’s time, presidential debates took place over hours in a packed auditorium. Postman recounts how, on at least one instance, Lincoln suggested in the middle of an hours-long debate that the audience should go home, eat dinner, then come back for another few hours. And the audience happily agreed! Whereas today, presidential candidates are lucky to get 2 minutes to answer a question and 1 minute for follow-ups or clarifications. The notion that one could lay out one’s comprehensive foreign policy agenda or meaningfully respond to an opponent’s plan for the economy within the span of just a few minutes is absurd!

So in place of reasoned discussion, we get viral soundbites and clap-backs. In place of genuine engagement with the other side’s policies, we get carefully scripted answers, strategic dodges, and performances tailored to the camera. In a television culture, the political debate takes on an entirely new character. It becomes less about argumentation and more about projecting confidence, charisma, and quick wit. The result is a spectacle that values style over substance, where winning the news cycle matters more than having the best ideas or the most well-thought out plans. In this way, the medium doesn’t just transmit the message — it transforms it, shaping not only what is said, but how it is said, and ultimately, what the public understands about the choices before them.

Television works best for shallow content, for show business, for immediate gratification. Which is why Postman thought the filtering of everything through the lens of entertainment was making us “sillier by the minute” (AOTD, p.20).

I should pause here and acknowledge that while Postman painted a very grim and one-sided picture of technology, we can take his critiques seriously while at the same acknowledging that technology is awesome. Tools are awesome, and our species has literally always used them, to the point where some say they have shaped us as much as we have shaped them. Without phones and computers, so much of modern life would be inaccessible, or at least much less convenient, for billions of people. Without television or social media, there’d be no music videos or viral memes, and many important social and political movements would have had a much harder time getting off the ground. Heck, without the printing press, education and knowledge would have remained limited to a privileged elite (though the democratization of learning relied also on changing social, political, and moral values).

Postman, too, recognized the obvious benefits of new technologies, and I doubt he’d choose to turn back the clock on progress if he could. He was a critic, not a dogmatic doomsayer. His gripe was not with technological progress per se, but rather with the unquestioningly positive attitude that modern society (particular in America) had towards it.

“Every technology is both a burden and a blessing; not either-or, but this-and-that.”

- Neil Postman

In “Technopoly”, Postman argues that societies exist on a continuum from tool-using cultures to Technopolies. In tool-using cultures, tools are invented and used, on the one hand, to solve specific material problems of daily life (cookware to safely and efficiently prepare food, eyeglasses to aid those with poor eyesight), and on the other hand to serve existing social and cultural institutions (like how the mechanical clock was invented to regulate and standardize the rituals of monks). Tool-using cultures have clear rules around when and how their tools are to be used, “subject to the jurisdiction of some binding social or religious system” (Technopoly, p.24).

As cultures shift from tool-users to technocracies (the intermediate stage on the continuum), technology begins to have more sway over existing social and cultural institutions. While the mechanical clock was originally used to support monastic life, it eventually spread to the general public, and its conception of time began to order all facets of public life and economic activity. Still, “citizens of a technocracy knew that science and technology did not provide philosophies by which to live” (p.47) and therefore still clung loosely to “the philosophies of their fathers”.

Postman argues that, at least in America, we have shifted from a technocracy to a Technopoly, in which the demands for efficiency and technique supersede all preexisting human values. Technology is seen as autonomous and sovereign, and its logic takes precedence over human judgement in the ordering of economic activity, the diagnosing of social and personal ills, and the shaping of public and even private life. In such a culture, traditional sources of authority and meaning are displaced by technical experts and the imperatives of technological systems. Human subjectivity is seen as a weakness as machines are granted sovereignty over all human affairs. We trust them more than we trust ourselves.

A Technopoly champions “progress without limits, rights without responsibilities, and technology without cost”. Its story is one “without a moral center”, its only values “efficiency, interest, and economic advance” (Technopoly, p.179).

"Technology giveth and technology taketh away."

- Neil Postman

There’s understandably a lot of talk right now about the harms of the modern digital environment. But at the same time, new technologies clearly deliver a ton of benefits. I, for one, love the digital Swiss army knife that is my iPhone. It’s undeniably cool that I can fit in my pocket a device with the combined capabilities of a telephone, television, computer, camera, notepad, and so much more. Don’t ask me to navigate a new city without Google Maps. And don’t ask me to recall my availability for the next two weeks without allowing me to pull up my calendar app. My phone is an extension of my mind, and I like it that way, dammit!

But throughout his work, Postman emphasized the need for balanced discussion among the abundance of hype. It’s not that we should only be pessimistic about technology, but simply that “a dissenting voice is sometimes needed to moderate the din made by the enthusiastic multitudes” (Technopoly, p.5). When we’re able to see how “Every technology is both a burden and a blessing; not either-or, but this-and-that”(p.5), we can approach technological change with eyes wide open. We can decide for ourselves how we want to implement technology to strategically advance human interests.

Importantly, Postman stressed that our last defense against Technopoly, against the subversion of human values to the demands of technique and efficiency, is education. While technocratic education systems aim to pump out graduates “with no commitment and no point of view but with plenty of marketable skills” (Technopoly, p.186), what education should do is instill in our youth a deep understanding of our species’ cultural, intellectual, religious, and moral roots. This is not only to help them comprehend their own history and the contingency of our current societal landscape, but also to unite them around a deeper purpose, to give them something other than wealth and hedonistic pleasure to aim towards in life. As Postman wrote, “our youth must be shown that not all worthwhile things are instantly accessible, and that there are levels of sensibility unknown to them. Above all, they must be shown humanity’s artistic roots” (p.197). It is therefore imperative that students be given a strong foundation in the arts and humanities, which are increasingly under threat.

"Our youth must be shown that not all worthwhile things are instantly accessible, and that there are levels of sensibility unknown to them."

- Neil Postman

Neil Postman repeatedly declared that “Technology giveth and technology taketh away.” As we barrel into an increasingly technological future, we would do well to keep in mind his decades-old insights — that media can shape our thoughts and behaviors beyond their content; that new technologies can subtly redefine older concepts like political debates, often in adverse ways that go unnoticed until it’s too late; and that we should be wary of letting technology encroach on domains where it doesn’t belong.

I’ve done my best here to summarize the core insights of “Amusing Ourselves to Death” and “Technopoly”, but I’m sure I left out much nuance and probably mischaracterized some things. For that reason I’d suggest reading these works for yourself, approaching them with an open mind and a willingness to learn, whether or not you agree with everything Postman has to say. I’d also recommend engaging with contemporary techno-critical authors like Nicholas Carr, whose books and articles (see especially “The Shallows” and “Superbloom”) give McLuhan- and Postman-esque critiques of the Internet and social media; and Cal Newport, whose concept of “digital minimalism” offers what I regard as a kind of psychotherapy for cyborgs.

The question isn't whether technology is "good" or "bad" — such binary thinking misses the point entirely. Instead, we should ask: How are our tools reshaping our psychic habits, social lives, and political and economic institutions? What might we be sacrificing at the altar of efficiency? Are we still capable of distinguishing between what technology can do and what it should do? And, most importantly, what does technology giveth, and what does it taketh away?

This was such an incredibly smooth, read. Insightful and thought provoking.