Time-Blocking: A Student's Tool for Calm and Concentration

This time management system is a godsend for burnt-out office workers. And for busy students too.

I recently graduated from Williams College, which I find myself reflexively describing as “a tiny liberal arts school in Western Massachusetts” whenever someone asks, as if reciting a well-worn script.

While at Williams, I, like many of my peers, balanced a variety of commitments: research fellowships, study abroad, TA’ing a course, extracurricular performances in dance and music, and a 75-page senior thesis. Using Cal Newport’s methods for time-block planning*, I maintained strong performance throughout my pursuits without ever pulling an all-nighter. In fact, I rarely worked very late into the night at all.

Time-blocking helped me excel in college while maintaining clear boundaries around study time. This opened up critical time and space for ideas to breathe, and for developing hobbies, exploring interests, and just enjoying student life.

*Newport didn’t invent the idea of time-block planning, but he helped popularize and refine it.

Stetson Hall, Sawyer Library. Williams College.

Time-block planning can be done on a scrap of paper or in one of Newport’s specially designed planners. It involves dividing your day into blocks of time and assigning to each block a specific, meaningful task or group of tasks you want to make progress on. Blocks range from 30 minutes to several hours.

This system can be particularly helpful for knowledge workers like researchers and creatives, whose tasks primarily involve processing and manipulating information as opposed to physical goods. This type of work demands sustained focus and concentration on complex, often abstract information.

The typical knowledge worker not only has massive amounts of cognitively demanding tasks on their plate, but they’re also rarely given any guidance on how to approach these tasks. Without such guidance, the path of least resistance is a reactionary, ad-hoc approach to work that often leads to feelings of burnout and overwhelm. It can feel like the work never ends.

The standard daily operating procedure for many college students goes something like this:

Wake up twenty, maybe thirty minutes before your first class. Go to class, piddle about for a few hours until your next one. Piddle about some more after that class. Finally get back to your dorm and check to see if you have anything due this week. Oh — there’s a paper due in two days. Get started on it (maybe after a ‘quick’ glance at email or TikTok). Over the next 48 hours, do whatever it takes to finish the paper, even if it means sacrificing sleep or self-care.

I know; I’ve been there.

Contrast that with the standard daily operating procedure for a college student who uses time-block planning:

The whole process actually starts the night before. Before winding down for the day, open up your calendar and transfer all of tomorrow’s scheduled activities (classes, meals with friends, club meetings, etc.) onto their designated time in your time-block planner.

Note the spaces in between. See on your calendar or whatever system you use to keep track of your duties and deadlines (e.g., Notion) that you have an essay or problem set due at the end of the week. Maybe you can stake out a spot in the library in between classes to get cracking on that. Note that in the planner. Notice an empty block of time between your last class of the day and your dinner with a friend. Perhaps you can block in a nap during that time, or, if you’re feeling particularly motivated, you can use that block to do “shallow” work like answering emails or making phone calls.

The first approach is reactive; the second, proactive. One is harried; the other, empowering.

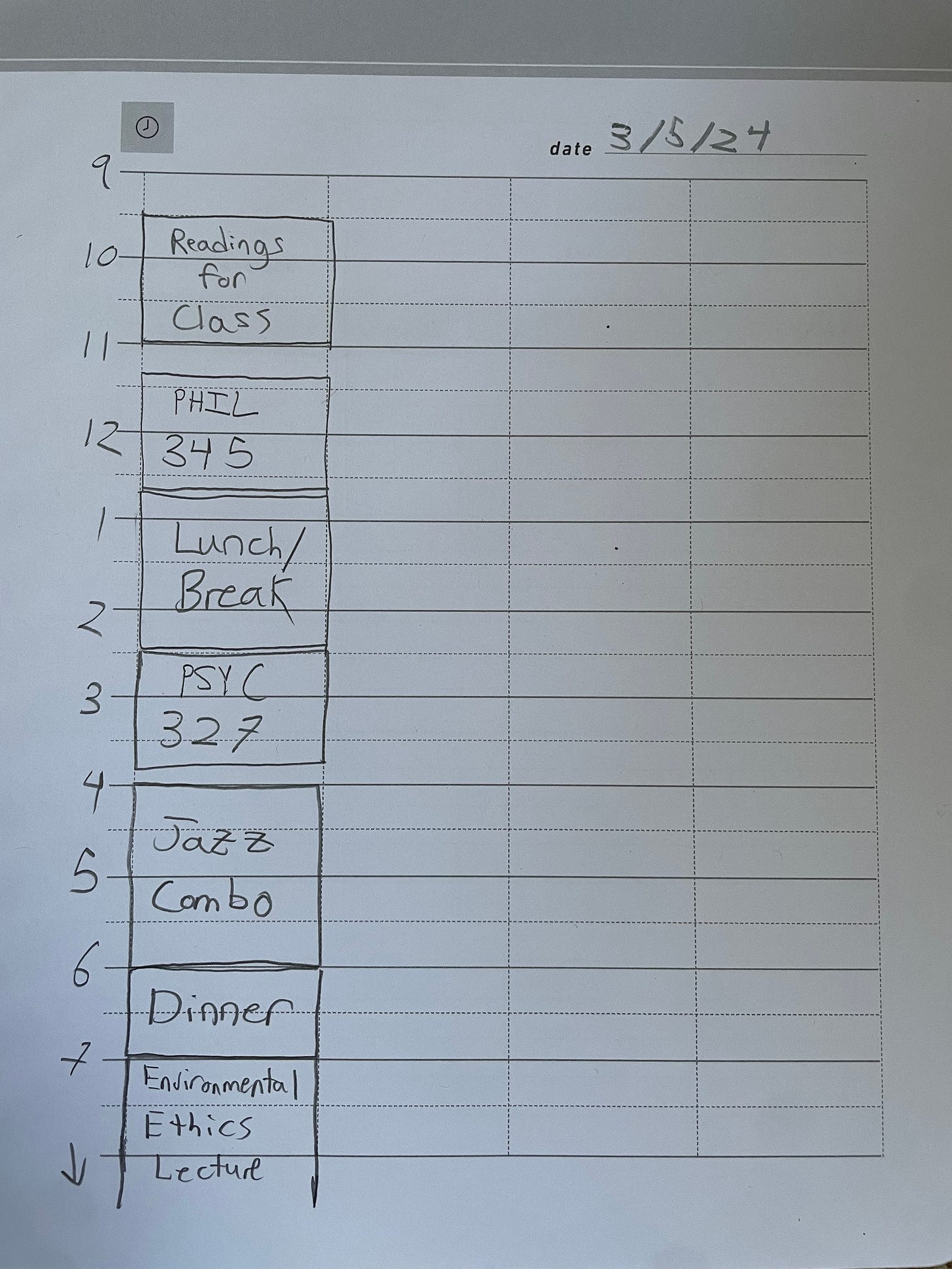

I used the second approach to plan most of my weekdays at Williams. On a particularly busy day of my senior year, for example, I might start the morning with a study block. After class, I’d give myself an hour or more for lunch break. I tried to make these breaks real breaks, not ones when where I was checking my email or glancing at assignments. Afterwards, I’d go to my next class, then an extracurricular, then a lecture after dinner.

This is what the time-block plan for that day would look like:

That’s a full, busy day. But it was also very clear, at each moment in the day, what I was supposed to be doing. This largely helped mitigate the anxiety and cognitive fatigue of constantly wondering what to do next, whether I’m doing ‘enough’, whether I’m doing what I’m ‘supposed’ to be doing. Eschewing these worries allowed me to be fully present in my activities and hone in with laser-like focus on the work that actually moved the needle forward.

“If you control your schedule: (1) you can ensure that you consistently dedicate time to the deep efforts that matter for creative pursuits; and (2) the stress relief that comes from this sense of organization allows you to go deeper in your creative blocks and produce more value.” - Cal Newport

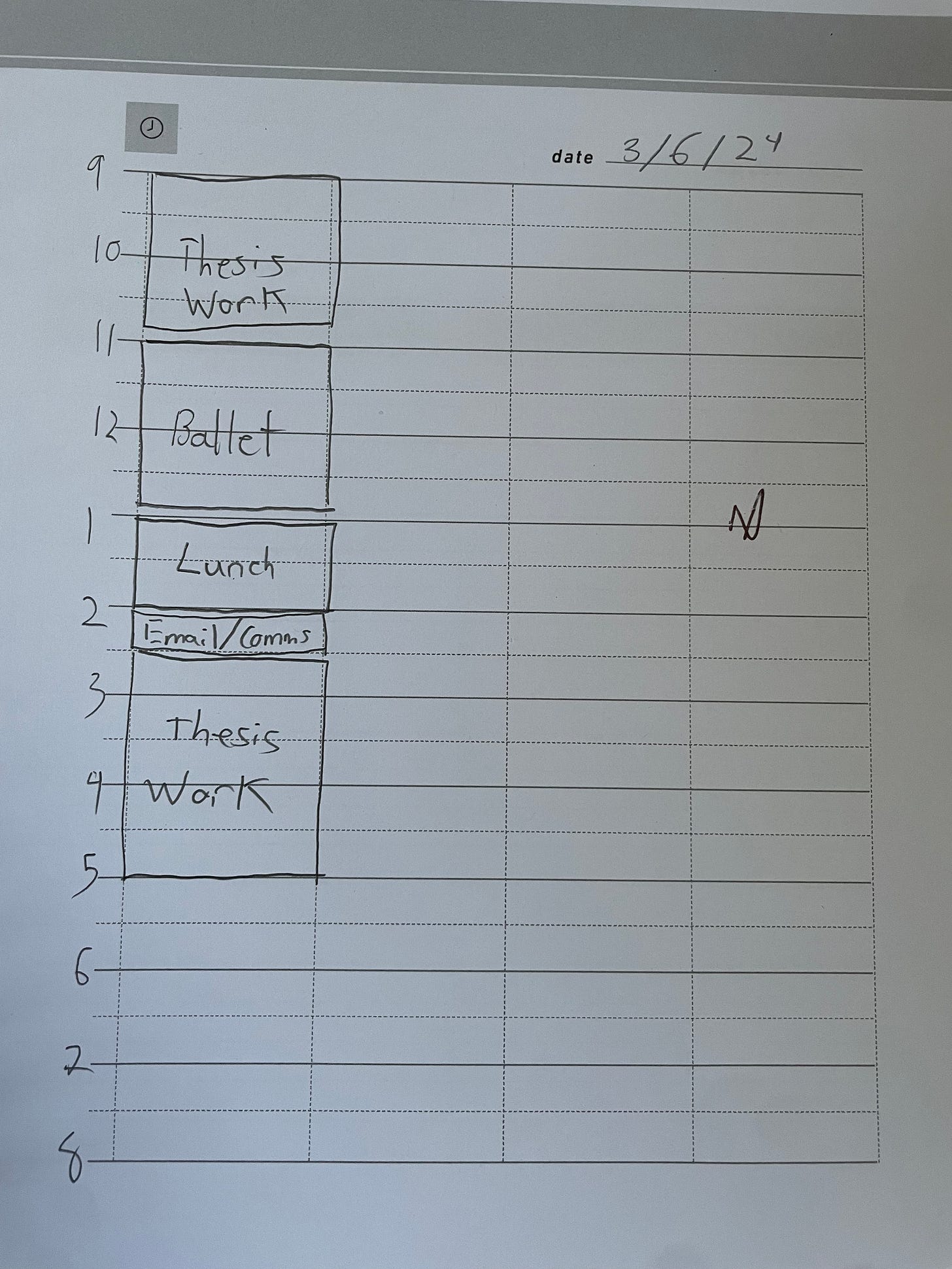

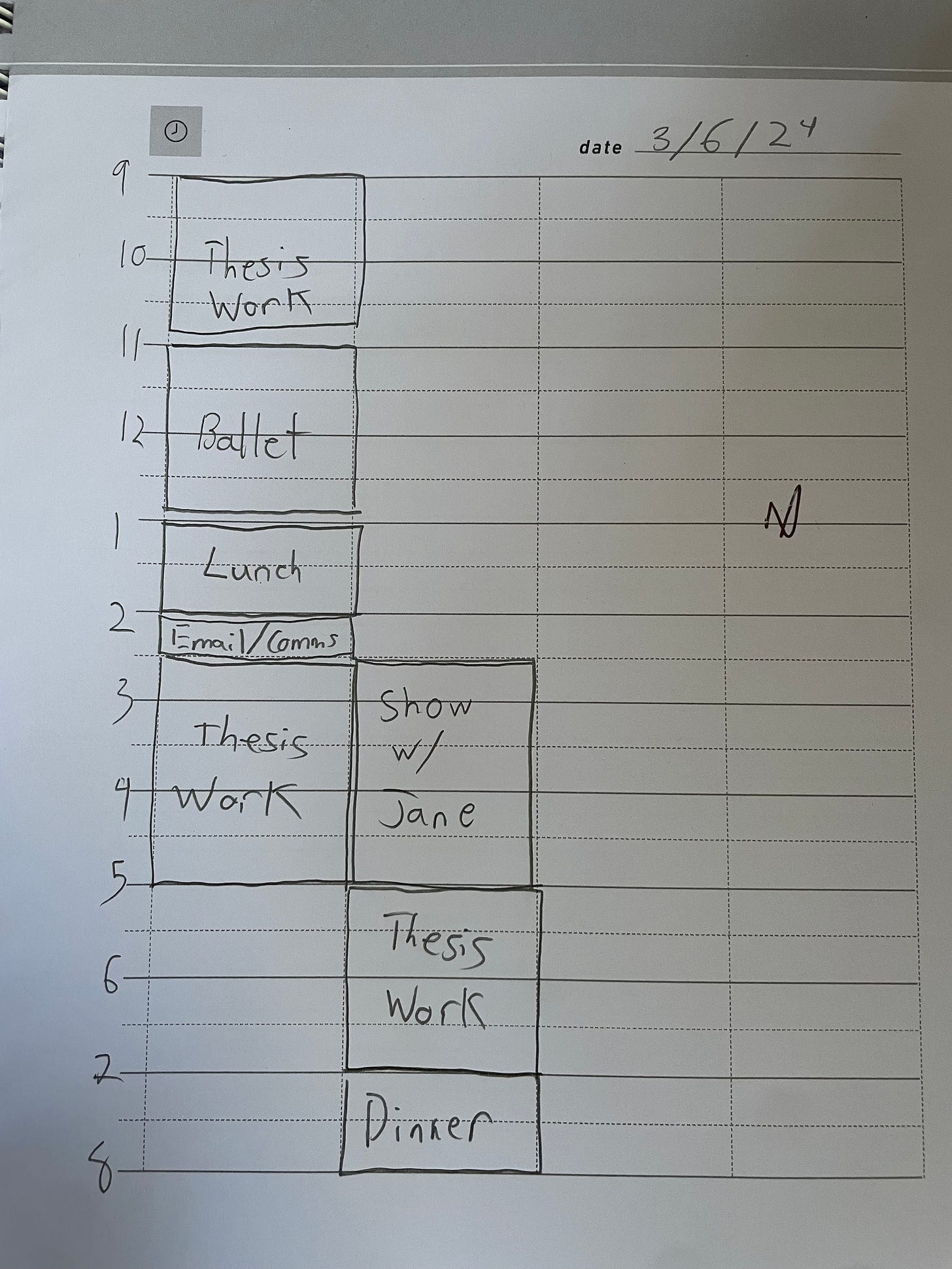

On lighter days during less demanding periods of the semester, I scheduled in more deep work blocks during the day so I could make progress on important but non-urgent tasks (like writing a thesis). I often happily left my evenings open and undefined.

What if my plans changed mid-day? No problem. The extra columns in the time-block planner are for revising the original schedule as the day unfolds, like so:

Time-block planning in college helped me make the most of the hours in between my scheduled commitments, freeing up most evenings for hobbies, sleep, and other extracurricular activities. Of course, there were still occasional late nights and early mornings, but I have a feeling their frequency was greatly reduced thanks to careful planning.

One thing I learned from time-block planning through college is that there’s actually a lot less time in the day than we tend to think. I found that in order to make meaningful progress on cognitively demanding tasks, I generally needed to block out at least an hour or two to allow ample time for my mind to settle into the kind of calm, focused state such work requires. Once I’d blocked in my scheduled commitments, I had to be very intentional about the spaces in between if I wanted to finish work at a reasonable hour.

Time-block planning also gave me a way to contain the shallower, but still necessary, parts of being a student: answering emails from professors, applying for opportunities, reaching out to friends and colleagues. Most days, I’d have at least one 30-minute block dedicated to tasks like these.

As I begin my graduate studies and seek employment, I plan to continue using time-block planning, though I’m sure I’ll have to continually adapt my approach as my responsibilities shift and accumulate. That’s perfectly fine. The point of time-block planning isn’t to rigidly follow your intended schedule to a T. Rather, it’s to provide structure and intention to your day, allowing you to prioritize important tasks and allocate appropriate time for them.

If, like me, your aim is to produce high-quality knowledge work without sacrificing your wellbeing, then it’s worth giving time-block planning a try.

Any questions about time-block planning or my broader approach to time/task management? Leave a comment!

I definitely could have used this strategy when I was in college! This strategy is a life saver. I love how you explained it with examples of how you implemented this in your daily life. You make things easy to understand and apply.

This is great! I'm familiar with some of Cal Newport's writing, but I often fail to put those strategies to use in my own work. Your discussion is inspiring me to commit to giving it a serious try in the fall semester!